Organisational Changes Associated with the LSP

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

Although the LSP was largely viewed as a technical project, there were significant organisational implications. In the longer term, the project could impact on the way in which legislation is enacted, though these implications have been minimised in the shorter term. Particularly, the development of the system has affected the technical/ process infrastructure, roles, authority structures and culture of the OPC.

Changes in the Process of Enacting Legislation and Broad Organisational Changes

On one level, the LSP produced minimal wider changes, but in specific areas, it has, and probably will induce significant changes.

Technological developments in public administration tend to be complex as a result of inevitable inter-weaving of political, judicial and technical aspects (Snellen and Schokker, 1992). The developers of the LSP coped with this increased complexity by avoiding it. In other words, they avoided having to deal with the broad contextual issues and cope with the corresponding risks by carefully embedding the project in the outer organisational context. Thus, changes directly resulting from the system on the broader parliamentary procedures are minimal.

However, the project was predicted to greatly impact on the legislation drafters and their support staff, and the bulk of the description here focuses on this level of analysis. Broadly speaking, the purpose of the OPC and its place in its wider organisational context have not changed. However, there have been some significant specific changes, including:

-

Changes to the evidentiary status of electronic documents. When the EnAct system was implemented, legislation was stored in a consolidated, electronic format and there were concerns that the legality of this legislation could be questioned. Originally, the Solicitor General believed the source document, which would be the definitive source of law, would still be the original hard copy Act filed in the Supreme Court. Thus, initially the Solicitor General tried to fit the changes to the established norms of keeping official versions of documents on chapter. Later it was decided that electronic copies of legislation should be given at least equivalent status to printed copies, and prima facie be evidence of the written law as of a given date.

-

Changes in the process of forwarding legislation to the Printing Office and the process of printing legislation. The LSP has significantly reduced the role of the Printing Office. Whereas previously they created the final version of legislation, which was proofread by the OPC, the OPC now provide them with a camera-ready version. With the launch of a web site to access the EnAct system (see www.thelaw.tas.gov.au), there is also far less need for printed legislation.

-

Changes in how government agencies and the public access legislation. Publicly accessible consolidated legislation allows lawyers and other users of legislation to reduce costs by eliminating the need to maintain manual paste-ups of legislation and enabling electronic text searching. This is impacting on the roles of those who have been responsible for such paste-ups.

These changes, although significant in their own right to those involved, are minor compared with the potential changes which could emerge. These include changes to:

-

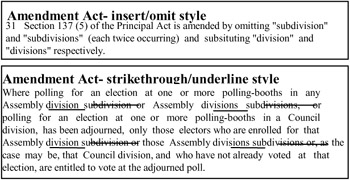

The methods by which Parliament and instructing agencies receive legislation for review. Currently, Parliament receives amendments in an insert/omit format, as illustrated in Figure 1. An alternative strikethrough/underline presentation, also illustrated in Figure 1, would allow parliamentarians to view proposed amendments in context and so could improve the effectiveness of Parliament.

Figure 1: Insert/Omit and Strikethrough/Underline Styles. -

Tasmania's legislation Consolidation of Acts within EnAct highlighted a number of errors, many of which were simply grammatical, but some which were significant (one Act was found to refer to a "minister of faeces"). Consolidation may stimulate changes to the statute book.

-

Improved access to legislation by lay people, as specific legal expertise and considerable time is not required to consolidate legislation.

-

Greater efficiency by government agencies and legal organisations, who are no longer required to maintain their own pasted up versions of legislation. Units such as the Audit Office and Police spent considerable effort in maintaining their own copies of legislation.

Nature of Work Processes (Technical and Process Infrastructure)

The LSP has not greatly changed the process of enacting legislation. This would have involved substantial re-engineering of parliamentary processes, and this probably would not have been successful. Parliamentary processes aim not so much for efficiency, as is the focus of BPR activities, but the amalgamation of different opinions and interests into policies. Any alteration to workings of parliament could be interpreted as a threat to the existing balance of power between the different political groups in parliament and the resulting debate would probably be significant and lengthy. Any BPR exercise is likely to challenge existing power bases but, in this case, the issues would have been magnified in that the status quo is the formal system of government.

However, there were significant changes to drafting processes. For example:

-

Amendments are created using EnAct to "mark up" the relevant principal legislation.

-

Drafters can electronically search consolidated legislation.

-

Some drafting tasks, such as repealing legislation, will only be able to be completed using EnAct.

-

Indexes of Bill and Statutory Rule numbers, Acts, cross references contained in Acts, and so forth, previously maintained by the OPC's records clerk, are not necessary with the new system.

One of the most significant changes was standardisation, especially in the wording of amendment legislation and the processes surrounding the creation of legislation. Standard wordings were required if the new system was to automatically produce amendment legislation from the consolidated legislation in which the drafters marked desired changes. Many discussions were held during the design stage to determine what the standard wordings would be. Through the analysis of LSP business rules, on which the new system was based, OPC standard practices were defined. In other areas, the project promoted standardisation but did not enforce it. Further examples of standardisation in relation to the LSP are provided in Table 1.

| Date occurred | Examples of standardisation associated with LSP |

|---|---|

| 6/9/94 | Standard interim formats for drafts discussed, and standard amendment wordings. |

| 4/11/94 | Agree on standard letters and forms, glossaries, macros, templates. |

| LSP processes described based on business rules. | |

| 14/11/94 | Development of standard forms for OPC. |

| 9/12/94 | Process charts for camera ready processes- though deputy chief drafter says these do not define "thou shalt do this". OPC now only accept maps and charts in particular formats. |

| 27/1/95 | Project manager says drafting will become more standardised with the new system (though later recognise need to override system 23/8/95). |

| 1/9/95 | Standardisation of statutory rules structures. |

| 22/11/95 20/12/95 | Standard wordings for amendments discussed; CPC comments that "The name of all this game is we are trying to build some consistency into the way we do things". |

| 5/9/97 | Impact analysis report: "EnAct provides a series of steps which represent the logical work flow for the preparation and processing of legislation..." "The entering of the legislative text can be performed in a creative "free form" manner, or by adding each piece of legislation in its final format... Regardless of the method used to draft the legislation, it needs to be modified into the correct structure before it can be converted into SGML" (pp 24-5). "Legislation is loaded on the consolidated database by a commencement utility... As the integrity of the legislation database is based on the commencement dates, the process needs to be completed accurately" (p 31). |

Role Changes

Importantly, many of the OPC's administrative tasks were to be eliminated, significantly reduced or substantially changed by the new system. Everyone was assured their jobs would not disappear, but that their nature may well change.

Burris (1993) suggested that computerisation is associated with greater distinction between expert and non-expert sectors, and so reinforces technocratic tendencies. With the implementation of EnAct, the systems developers predicted that people in the office would become more multi-skilled, and divisions between the two groups could be reduced. There has been little evidence of this, except in the role of the new systems administrator. This may be because previously, while there was a strict division between the drafters and the administrative staff, most of the administrative staff were considered experts in particular areas. The administrative staff generally had knowledge about the structure and format of legislation. When discussing keyboarding, drafters recognised the skills of the administrative assistants, and regarded them as experts. The EnAct system seems to be broadening the role of the administrative assistants at the same time as removing this area of specialisation by providing keyboard training to the drafters. Thus, observations of the LSP do not back up Burris' conclusions in this respect.

Barley (1990) suggested organisa-tional change cannot be seen to have occurred if there are no role changes. The roles of some of the support staff are changing or will probably change. The Executive Officer is taking on the role of system administrator. The roles of the administrative assistants and records clerks remain unclear, and will depend on how the drafters utilise EnAct in the longer term. However, it is apparent their skills will still be required. Far from being threatened with job loss, the administrative assistants have been required to both input previous legislation and support the drafters as they create current legislation. They have done this while learning to use what is widely agreed to be a very complex and sophisticated system.

The most fundamental change will be written legislation in a form that allows easier access to both consolidated and unconsolidated versions of acts, as acts and amendments are linked electronically. On the surface, this would suggest that the way the drafters create legislation could substantially change and that the roles of the administrative assistants would become redundant. Yet this is not necessarily so. It is possible for a drafter to not change the way they work greatly, so that the role of the administrative assistants expands to include the "marking up" of drafts into the required SGML formats (i.e., including structural tags in the writing). Some of the systems developers have anticipated some drafters may not change their work-practices with the implementation of the new system. Several drafters commented that they will still rely on the administrative assistants to complete large quantities of typing or to mark up and convert the drafters' work into required EnAct structures. Such role changes are still emerging and this remains an area for future research. Essentially, role changes are being negotiated on an ongoing basis as staff learn how to use the system and it becomes embedded into organisational processes.

Changes in the Formal Authority Structures

Those involved in the project claimed the LSP would empower OPC staff to have more control over their work, and would give the management of the OPC more control over the work of the staff. Paradoxically, both predictions seem to have occurred.

The systems developers believed EnAct could help break down the division between drafters and their support staff, as the support staff gained specialist skills and became more multiskilled. With the implementation of the system, the executive officer took on the role of systems administrator, a position that was to give him greater authority. Several other staff members gained authority by having knowledge about particular aspects of the system. In some ways, therefore, the LSP has helped break down the strict separation between the "specialist" drafters and their "support" staff.

At the same time, the drafters were concerned that administrative staff would be able to tell the drafters to conform to standards. They felt this impinged on their area of responsibility and would devalue their experience and hard-earned expertise.

With standardisation embedded in the EnAct system, the management of the OPC could impose standards on the staff of the OPC and so broadly control their work practices and outputs. Of course, most staff had input into the creation and interpretation of these standards. That is, control occurred not only from the top of the office downwards, but over time, as people helped develop standards they would later apply themselves. The new system also provided reporting facilities for the chief drafter to obtain information about drafting files within the office and workflow tools to monitor the progress of each legislative drafting task. Orlikowski (1988) suggested the introduction of computerised technology signals a commitment to systems thinking, and that control can be embedded in such systems. Her conclusions are echoed here.

Cultural Changes

Perhaps the biggest change was change itself. The OPC was a stable organisation whose work processes had not changed for some time. At the beginning of the LSP, staff members generally had little experience with computers and were not overly enrapt in the ideas of the systems developers. One of the systems developers politely referred to the "traditional nature of the OPC". A drafter likened himself and his colleagues to dinosaurs and the systems developers to mammals, thus humorously suggesting he felt threatened. Other drafters and support staff also often suggested they were uncomfortable with the technological changes being promoted. This impacted on how the systems developers approached the systems development process:

The OPC are not taking an active role (responsibility) for specifying their system requirements. The OPC will be required to "sign-off" the Functional Specifications as being an accurate representation of their system requirements. However, this stage is a little late for an effective contribution. The attitude seems to indicate a denial of change. The availability of the drafters' time is a constant issue. A phased implementation (of both technology and procedures) is emerging as the only plausible option (LSP Update, 15/3/94).

At times the systems developers extended their own cultural norms into the OPC. For example, the systems developers heavily emphasised the importance of documentation and systematic processes. At this stage, it is difficult to see if these imported norms will continue and if changes in the OPC's authority structures will result in cultural changes. Certainly, some OPC staff members felt the systems developers were promoting their own approach and viewed it as "cultural imperialism". On the other hand, others suggested that, as the office's heavy workload precluded OPC management's ability to focus on the quality and efficiency of office procedures and practices, it was beneficial to have some external input.

|

| < Day Day Up > |

|

EAN: 2147483647

Pages: 207